We typically think of educational institutions as systems. To think of schools as “systems” means to apply a machine metaphor to school operations, where there are certain “inputs,” which are used by people via “processes,” which lead to short and long term “outcomes.” And in thinking about how systems theory would apply to evaluation, we would use terms like “black box evaluation” to try to think about how we would identify the variables that would lurk around between key “inputs” and “outcomes,” and use statistical models to identify relationships among these variables.

But more recently, theorists and practitioners alike are starting to view educational institutions through the lens of complexity theory, using the biological metaphor of an organism. Complexity theory is thought to better describe the nature of educational institutions because schools tend to behave like complex adaptive systems, where “independent elements (which themselves might be made up of complex systems) interact and give rise to organized behavior in the system as a whole” (e.g., Am, 1994), and “order is not totally predetermined and fixed, but… is creative, emergent (through iteration, learning, and recursion), evolutionary and changing, transformative and turbulent” (Morrison, 2002).

Complexity Theory in a Nutshell

A quick summary of the difference between our conventional wisdom about systems and complexity theory is shown in the table below, adapted from Morrison (2002):

Conventional wisdom versus complexity theory

Adapted from Morrison (2002, p. 9)

To view schools as complex adaptive systems means we must accept that there may not always be a linear cause and effect relationship between initial conditions and outcomes, and that systems will evolve and emerge in unpredictable ways. Such a view has implications for how we evaluate not only the relationships between the variables that we value in school contexts, but what is worth measuring and evaluating in the first place.

Contingency Framework for Measurement in the Face of Complexity

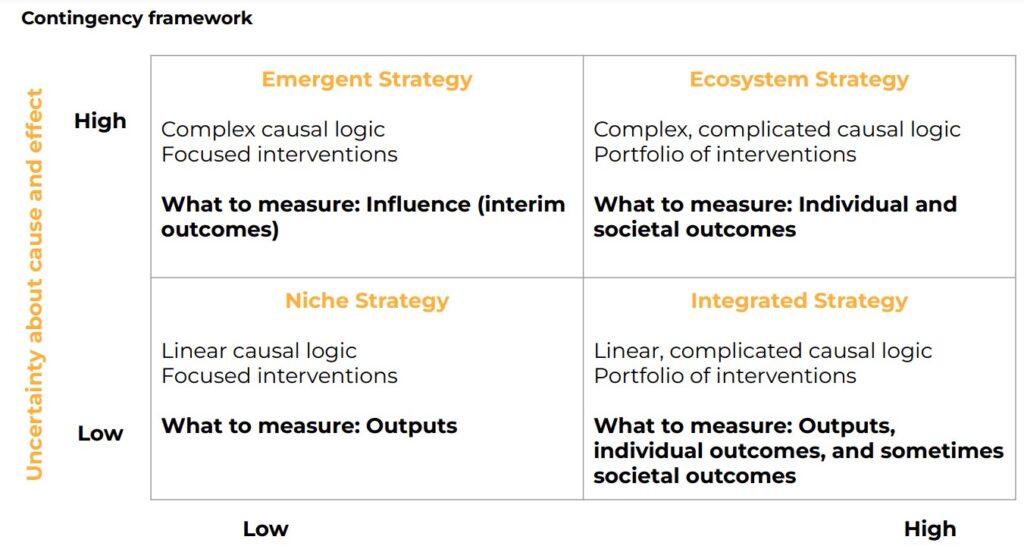

To help us think through what is “worth measuring” in the face of complexity, Ebrahim (2019) offers a contingency framework of measuring change. This contingency framework enables us to identify the level of uncertainty we have about cause and effect relationships and control over outcomes, and craft a measurement and evaluation plan accordingly.

Application of the contingency framework starts with an understanding of your role in the ecosystem and the outcomes you are trying to achieve. If you have a low level of uncertainty about cause and effect, and a low level of control over the outcomes, you would develop a niche strategy, using focused interventions, to contribute to improvements in outcomes, but would focus your measurement on your key outputs. If you have a high level of uncertainty about cause and effect, and a low level of control over the outcomes, you would develop an emergent strategy, using focused interventions, and would focus your measurement on your influence, or what we typically call “interim outcomes.” If you have a low level of uncertainty about cause and effect and a high amount of control over outcomes, you would develop an integrated strategy, using a portfolio of interventions, and measure outputs, individual outcomes, and sometimes “societal outcomes.” And if you have a high level of uncertainty about cause and effect but a high level of control over outcomes, you would develop an ecosystem strategy, using a portfolio of interventions, and measure individual and societal outcomes.

Contingency framework for measuring change

The Contingency Framework in Schools

There are many ways we can interpret this framework for school contexts. It would not seem unreasonable for schools as a whole to accept that they have a low level of uncertainty about cause and effect, yet a higher amount of control over outcomes, which means they would adopt an integrated strategy, using a portfolio of interventions (e.g., curricular, instructional, support, leadership, and operational), and measure their key outputs, individual outcomes (student outcomes), and sometimes societal outcomes (i.e., long-term, post-graduate impacts).

For leaders who lead functional roles one step removed in school district offices, such as professional learning, instructional technology, curriculum, or other supports, it may also make sense to think about the ultimate results these roles are trying to achieve within their district as a whole, their level of uncertainty and control, and then measure accordingly. For such supporting roles, there is often a high level of uncertainty about cause and effect, and a step removed from control over outcomes. This means that developing an emergent strategy with focused interventions (which is what these leaders already do well each and every day) and measuring the effects of those particular interventions becomes the most urgent priority. Focusing on the immediate influence (interim outcomes) of their particular internal offerings and services grants permission for these leaders to prioritize how to best use their precious resources, including time and effort spent in data collection, reporting, and goal-setting.

“Immediate Influence”

In instances where we seek to evaluate the immediate influence of professional learning, we often focus on measuring changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, aspirations, or behaviors (or KASABs) (Killion, 2017) and other organizational changes (Guskey, 2000), which we hope will inevitably translate to changes in student outcomes.

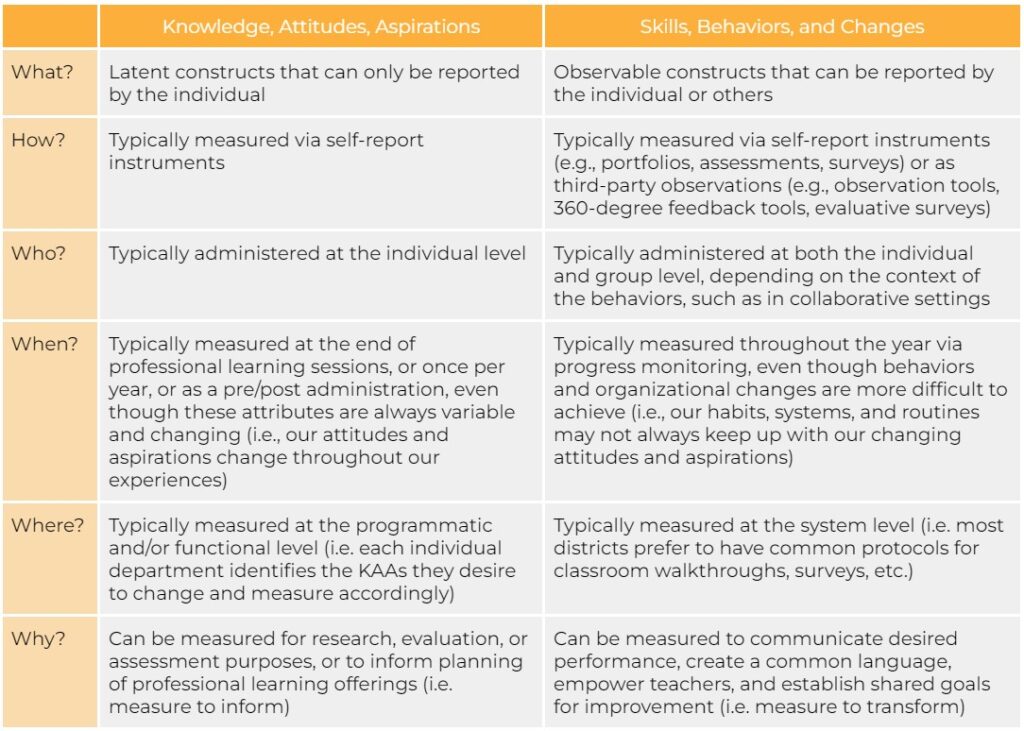

But there are some key differences between the measurement of knowledge, attitudes, and aspirations (KAAs) and the measurement of skills, behaviors, and organizational changes (SBCs) that should be taken into account before prioritizing which is most important to a particular change initiative. The way that these typically differ is illustrated in the table below.

The typical KASAB(C) measurement landscape

As is suggested in the Why? row of the chart above, we typically measure knowledge, attitudes, and aspirations for research, evaluation, or assessment purposes, or to inform planning of professional learning offerings, understand needs, check in on progress, etc. At other times, we wish to communicate our key indicators throughout the organization, create a common language, empower teachers, and establish shared goals for improvement – all goals for which measurement of skills, behaviors, and organizational changes (SBCs) would be better suited. Getting clear on which purpose we have for each of these attributes can help us prioritize what to measure, and when to measure it.

Behaviors and Organizational Changes as Key Measures of Influence (or Interim Outcomes)

In my experience, most leaders would argue that although knowledge, aspirations, skills, and attitudes are important and worth attending to in any professional learning or change initiative, it is the behaviors and organizational changes that are most observable, indicate learning transfer, are what we most desire to reasonably take credit for as we lead change, and are theoretically linked to better learning experiences for students. We often seek to change knowledge, attitudes, skills, and aspirations only because we ultimately seek to change behavior.

It can also be said that we may wish to measure knowledge, attitudes, and aspirations to inform our work, but that we would desire to measure behaviors and organizational changes to transform our work. This means prioritizing the measurement of behaviors and changes as the key interim outcomes for any change initiative, whether it be through self-report instruments or as third-party observations. And since our purpose in measuring behaviors is to communicate desired performance, create a common language, empower teachers, and establish shared goals for improvement,, this means developing measurement tools that better accomplish these aims, such as maturity models, performance-based rubrics, collaborative assessments, and other innovative tools, and clever ways to administer them, whether they be through self-report or third party observations.

Such a laser-like focus on behaviors and organizational changes as the key interim outcomes of any change initiative or other professional learning effort helps us focus on measuring what matters in complex adaptive systems. Doing so may help us avoid fears that we are missing something in a “black box” world, and instead embrace, explore, and relish the myriad impacts of our efforts as they continually emerge in uncertain ways.

References

Åm, O. (1994). Back to Basics: An Introduction to Systems Theory and Complexity.

Ebrahim, A. (2019). Measuring Social Change: Performance and Accountability in a Complex World. Stanford University Press.

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin press.

Hiatt, J. (2006). ADKAR: a model for change in business, government, and our community. Prosci.

Killion, J. (2017). Assessing impact: Evaluating professional learning. Corwin Press.

Morrison, K. (2012). School leadership and complexity theory. Routledge.